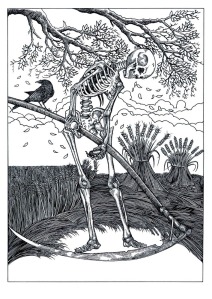

Whenever he came into the village, the children ran away. Women retreated behind locked doors. No one spoke to him if they could avoid it. His touch could corrupt you, and he had evil in his soul. If you needed him, he would come, and it was his work that had tainted him. He was a sin-eater, and he would help the dead enter paradise, though he would never set foot there himself.

The job of a sin-eater is an under-studied one. We know they existed in England and Wales, in Bavaria, the Balkans and Appalachia, but folklorists seem to have paid them little attention. References to them begin in the 18th century, although it seems likely that the practice began long before that.

Sin-eating is a funerary custom. It seems to have begun as a ritual performed for those who had died suddenly, without having a chance to confess their sins, and, in time, it became something that could be performed for anyone who had died.

“Two Old Men”, Francisco Goya

After a death, a sin-eater would be summoned. He would enter the room where the corpse lay, and a wooden platter or bowl with bread in it would be placed on the chest of the deceased. Sometimes beer was also given. The sin-eater would consume this ritual meal and, with it, take upon himself the sins of the dead person. He would be given a small payment for his services – often sixpence – and leave. The utensils he had used would be burned.

Each time his services were required, the sin-eater would take on more of the sins of others. He was sin-full, depraved, and avoided. He was “abhorred by superstitious villagers as a thing unclean…cut…off from all social intercourse with his fellow creatures by reason of the life he had chosen; he lived as a rule in a remote place by himself, and those who chanced to meet him avoided him as they would a leper…[He] was held to be the associate of evil spirits, and given to witchcraft, incantations and unholy practices.”[1] A macabre, and rather sad job to have.

Why would a sin-eater be wanted?

In Catholicism, someone who is dying should receive the Last Rites. These consist of a final confession of sin (Penance), which is followed by absolution – the forgiveness of those sins. After that comes Extreme Unction, the anointing of the body, followed by Viaticum, a final reception of the Eucharist (Viaticum means ‘provision for the journey’). Catholics are encouraged to pray not to have a sudden death, because that final confession is important. The Catholic Church’s catechism states:

CCC 1033: To die in mortal sin without repenting and accepting God’s merciful love means remaining separated from him for ever by our own free choice. This state of definitive self-exclusion from communion with God and the blessed is called “hell.”

Now, as it happens, dying without being able to make a final confession of sin is not something that means the person will go to hell, because if the person genuinely wants to confess, not because of the fear of hell but from love of God (perfect contrition) and they have the intent to confess is there then absolution will be granted if they should unfortunately happen to die before being able to confess (CCC 1452).

That may be official teaching, but for many people, now and then, death without a final repentance and absolution means going to hell. Even beyond Catholicism, Protestant areas like England and Wales retained a sense that people should put their affairs in order and make themselves right before God in order to be assured of heaven.

And that is where the sin-eater comes in. If the unconfessed and unforgiven sins of the dead person could be transferred to someone else, then their soul would go to heaven, unencumbered. The sin-eater, though, had voluntarily chosen to go to hell, with the weight of the sins of many others on their soul. They had chosen damnation – which is why they were feared, for what other things might a person do, who had no fear of hell?

And that is where the sin-eater comes in. If the unconfessed and unforgiven sins of the dead person could be transferred to someone else, then their soul would go to heaven, unencumbered. The sin-eater, though, had voluntarily chosen to go to hell, with the weight of the sins of many others on their soul. They had chosen damnation – which is why they were feared, for what other things might a person do, who had no fear of hell?

There was another reason for sin-eating. It was (and is) believed that the dead might continue to walk the earth after they died, haunting the places they visited in life. Sin-eating contained the dead, and made sure they transferred to the hereafter, without troubling those left behind. The prayer of the last sin-eater, Richard Munslow, says,

I give easement and rest now to thee, dear man, that ye walk not down the lanes or in our meadows. And for thy peace I pawn my own soul. Amen.

Where did the idea come from?

It seems an odd practice to spring up out of nowhere, so where did the idea of transferring sin from one person to another come from?

The most obvious answer is simply, the Bible. In the Old Testament book of Leviticus, a ritual transference of the sins of the people onto a goat is described.

Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task. The goat shall bear on itself all their iniquities to a barren region; and the goat shall be set free in the wilderness. (Leviticus 16:21-22)

For Christians, Christ is “the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world” (1 John 2:2) and he, like the scapegoat of Leviticus, had the sins of others transferred to him before his death on the cross.

A similar idea can be found in the confessions of accused witches during the early modern period. They, and their clients, believed that illness and disease could be transferred from a person to an animal, or object. Thus, during the North Berwick witch trials, Agnes Sampson confessed that she had eased the labour pains of Euphame MacCalzean, they were “cast off…upon a dog which ran away and was never seen again.” In 1597 in Aberdeenshire, Andro Man was accused of curing Alexander Simpson by putting him “nyne tymes fordwart throch ane hesp of unvatterit yarne, and than throw tuik a cat, and pat hir nyn tymes bakvart throw the sam hesp, and said thy orationis on him, and put on the seiknes on the cat, quha instantlie deit, and the said Alexander immediatlie recoverit of his disease.”

A Melancholy Occupation

The sin-eater had a sad and lonely existence. They helped others to a heaven they themselves would never reach, and for their sacrifice received only “a miserable fee and a scanty meal”. They were outcasts, doing something the church never approved of, avoided by their peers, tainted and unclean.

The sin-eater had a sad and lonely existence. They helped others to a heaven they themselves would never reach, and for their sacrifice received only “a miserable fee and a scanty meal”. They were outcasts, doing something the church never approved of, avoided by their peers, tainted and unclean.

I suspect that desperation drove the sin-eaters. Poverty, an inability to work, or perhaps a feeling that they were damned already. Most recorded sin-eaters were poor, but the last sin-eater, Richard Munslow, was not. He was a farmer, prosperous enough to hire two or three labourers. He was also a man who had lost first one child, in 1862, and then three more within the space of a week in 1870. Grief, and depression may have driven him to the practice, and perhaps compassion for the dead.

As far as we know, there are no sin-eaters today. By the start of the 20th century, the practice had died out, as people no longer believed in the transference of sin, or in the need for the faithful to seek it. I wish there was more known about the practice, about the sin-eaters and their lives, and the beliefs of those who hired them. It may not be possible, now, to find out more about them, but I think it would be a worthwhile thing to study.

Further Reading

- The Sin-Eaters and the Lost Sacraments – David Mills

- The Sin-Eater – Nantlle Valley History

- Richard Munslow’s Grave – Shropshire Churches Tourism Group

- Sin-Eating in Appalachia – The Lost Creek Medicine Show

- Funeral Customs – Bertram S Puckle

- Funeral Service for the ‘Last Sin-Eater’ – BBC News

- Scottish Folk Magic and the Dead – Cailleach’s Herbarium

- Sin-Eaters – Fortean Times Forum (including quotations and links)

- Sin-Eater – Wikipedia